The antitrust argument that says big tech needs breaking up to stop platforms abusing competition and consumers in a two-faced role as seller and (manipulative) marketplace may only just be getting going on a mainstream political stage — but startups have been at the coal face of the fight against crushing platform power for years.

Presearch, a 2017-founded, pro-privacy blockchain-based startup that’s using cryptocurrency tokens as an incentive to decentralize search — and thereby (it hopes) loosen Google’s grip on what Internet users find and experience — was born out of the frustration, almost a decade before, of trying to build a local listing business only to have its efforts downranked by Google.

That business, Silicon Valley-based ShopCity.com, was founded in 2008 and offers local business search on Google’s home turf — operating sites like ShopPaloAlto.com and ShopMountainView.com — intended to promote local businesses by making them easier to find online.

But back in 2011 ShopCity complained publicly that Google’s search ranking systems were judging its content ‘low quality’ and relegating its listings pages to the unread deeps of search results. Listings which, nonetheless, had backing and buy in from city governments, business associations and local newspapers.

ShopCity went on to complain to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), arguing Google was unfairly favoring its own local search products.

Going public with its complaint brought it into contact with sceptical segments of the tech press more accustomed to cheerleading Google’s rise than questioning the agency of its algorithms.

“We have developed a very comprehensive and holistic platform for community commerce, and that is why companies like The Buffalo News, owned by Berkshire Hathaway, have partnered up with us and paid substantial licensing fees to use our system,” wrote ShopCity co-founder Colin Pape, responding to a dismissive Gigaom article in November 2011 by trying to engage the author in comments below the fold.

“The fact that Google recently began copying our multi-domain model… and our in-community approach, is a good indication that we are onto something and not just a ‘two-bit upstart’,” Pape went on. “Google has stated that the local space is of great importance to them… so they definitely have a motive to hinder others from becoming leaders, and if all it takes to stop a competitor from developing is a quick tweak to a domain profile, then why not?”

While the FTC went on to clear Google of anti-competitive behavior in the ShopCity case, Europe’s antitrust authorities have taken a very different view about Mountain View’s algorithmic influence: The EU fined Google $2.73BN in 2017 after a lengthy investigations into its search comparison service which found, in a scenario similar to ShopCity’s contention, Google had demoted rival product search services and promoted its own competing comparison search product.

That decision was the first of a trio of multibillion EU fines for Google: A record-breaking $5BN fine for Android antitrust violations fast-followed in 2018. Earlier this year Google was stung a further $1.7BN for anti-competitive behavior related to its search ad brokering business.

“Google has given its own comparison shopping service an illegal advantage by abusing its dominance in general Internet search,” competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said briefing press on the 2017 antitrust decision. “It has harmed competition and consumers.”

Of course fines alone — even those that exceed a billion dollars — won’t change anything where tech giants are concerned. But each EU antitrust decision requires Google to change its regional business practices to end the anti-competitive conduct too.

Commission authorities continue monitoring Google’s compliance in all three cases, leaving the door open for further interventions if its remedies are deemed inadequate (as rivals continue to complain). So the search giant remains on close watch in Europe, where its monopoly in search puts special conditions on it not to break EU competition rules in any other markets it operates in or enters.

There are wider signs, too, that increasing antitrust scrutiny of big tech — including the idea of breaking platforms up that’s suddenly inflated into a mainstream political talking point in the U.S. — is lifting a little of the crushing weight off of Google competitors.

One example: Google quietly added privacy-focused search rival DuckDuckGo to the list of default search engines offered in its Chrome browser in around 60 markets earlier this year.

DDG is a veteran pro-privacy search engine Google rival that’s been growing usage steadily for years. Not that you’d have guessed that from looking at Chrome’s selective lists prior to the aforementioned silent update: From zero markets to ~60 overnight does look rather  .

.

Rising antitrust risk could help unlatch more previously battened down platform hatches in a way that’s helpful to even smaller Google rivals. Search startups like Presearch . (On the size front, it’s just passed a million registered users — and says monthly active users for its beta are ~250k. Early adopters skew power user + crypto geek.)

Google’s dominance in search remains a given for now but a fresh wind is rattling tech giants thanks to a shift in tone around technology and antitrust, fuelled by societal concern about wider platform power and impacts, that’s aligned with fresh academic thinking.

And now growing, cross-spectrum political appetite to regulate the Internet. Or, to put it another way, the tech backlash smells like a vote winner.

That may seem counterintuitive when platforms have built massive consumer businesses by heavily marketing ‘free’ consumer-friendly services. But their shiny freebies have sprouted a hydra of ugly heads in recent years — whether it’s Facebook-fuelled, democracy-denting disinformation; YouTube-accelerated hate speech and extremism; or Twitter’s penchant for creating safe spaces for nazis to make friends and influence people.

Add to that: Omnipresent creepy ads that stalk people around the Internet. And a fast-flowing river of data breach scandals that have kept a steady spotlight on how the industry systematically plays fast and loose with people’s data.

European privacy regulations have further helped decloak adtech via an updated privacy legal framework that highlights how very many faceless companies are lurking in the background of the Internet, making money by selling intelligence they’ve gleaned by spying on what web users are browsing.

And that’s just the consumer side. For small businesses and startups trying to compete with platform goliaths engineered and optimized to throw their bulk around, deploying massive networks and resources to tractor-beam and data mine anything — from product development; to usage and app trends; to their next startup acquisition — the feeling can be one of complete impotence. And, well, burning injustice.

“That was actually the real genesis moment behind [Presearch] — the realization of just how big Google is,” Pape tells TechCrunch, recounting the history of the ShopCity FTC complaint. “In 2011 we woke up one day and found out that 80-90% of our Google traffic had disappeared and all of these sites, some of which had been online for more than a decade and were being run in partnership with city governments and chambers of commerce, they were all basically demoted onto page eight of Google.

“Even if you typed them by name… Google had effectively, in their own backyard, shut down this local initiative.”

“We ended up participating in this [FTC] investigation and ultimately it cleared Google but we’ve been really aware of the market power that they have — and certainly what could be perceived as monopolistic practices,” he adds. “It’s a huge challenge. Anybody trying to do any sort of publishing or anything really on the web, Google is the gatekeeper.”

Now, with Presearch, Pape and co are hoping to go after Google in its techie backyard — of search.

Search, decentralized

Breaking the “Google habit” and opening up web users to a richer and more diverse field of search alternatives is the name of the game.

Presearch’s vision is a community-owned, choice-rich online playing field in the place where the Google search box normally squats; a sort of pluralist, collaborative commons that welcomes multiple search providers and rewards and surfaces community-curated search results to further diversity — encouraging Internet users to discover a democratized multiplicity of search results, not just the things big tech wants them to see.

Or as Pape puts it: “The ultimate vision is a fully decentralized search engine where the users are actually crawling the web as they surf — and where there’s kind of a framework for all of the participants within the ecosystem to be rewarded.”

This means that Presearch, which is developing a community-contributed search engine in addition to the federated search tool platform, is competing with the third party search providers it offers access to.

But from its point of view it’s ‘the more the merrier’; Call it search choices for customizable courses.

“Or as we like to think of it, like a ‘Switzerland of search’,” says Pape, adding: “We do want to make sure it’s all about the user.”

Presearch’s startup advisor roster includes names that will be familiar to the wider blockchain community: Ethereum co-founder and founder of Decentral, Anthony Di Iorio; Rich Skrenta, founder and CEO of startup search engine Blekko (acquired by IBM Watson back in 2015); and industry lawyer, Addison Cameron-Huff.

“When you’re a producer on the web you realize how much control Google does really have over user traffic. Yet there are thousands of different search resources that are out there that are subsisting underneath of Google,” continues Pape. “So we’re really trying to give them more of a platform that a lot of these different providers — including DuckDuckGo, Qwant — could get behind to basically break that Google dependency and make it easier for them to have a direct relationship with the their audience.”

Of course they’re nowhere near challenging Google’s grip yet.

And like so many startups Presearch may never make good on the massive disruptive vision. It’s certainly got its work cut out. Being a startup in the Google-dominated search space makes the standard hostile success odds exponentially harsher.

“Presearch is a highly-ambitious project,” the startup admits in its WhitePaper. “Google is one of the best companies in the world, and #1 on the Internet. Improving on their results, experience, and integrations will be no small feat — many even say it’s impossible. However, we believe that collectively the community can creatively and elegantly fulfill its own search needs from the ground up and create an amazing and open search engine that is aligned with the interests of humanity, not just one company.”

For now the beta product is, by Pape’s ready admission, more of a “search utility” — offering a familiar search box where users can type their queries but atop a row of icons that allow them to quickly switch between different search engines or services.

As well as offering Google search (the default search engine for now), DuckDuckGo is in the list, as is French search engine Qwant. Social platforms like Facebook and LinkedIn are also there to cater to people-focused queries. As is stuff like Wikipedia for community-edited authority. In all Pape says the beta offers access to around 80 search services.

The basic idea for now is to let users select the most appropriate search tool for whatever bit of info they’re trying to locate. Aka that “level playing field for a whole bunch of different search resources” idea.

This does look like a power tool with niche appeal — Pape says about a quarter of active users are actively switching between different engines; so ~75% are not — but which is being juiced, and here comes the crypto, by rewarding users for searching via the federated search field with a token called PRE.

Pape says users are provided with a quarter token per presearch performed — up to a cap of eight tokens per day. The current market value of the PRE token is around $0.05. (So the hardest working Presearchers could presumably call themselves ’40cents’.)

While there are ways for users to extract PRE from the platform if they wish, converting it to another cryptocurrency via community built exchanges, Pape says the intent is to create more of “a closed loop ecosystem”. Hence he says they’re busy building a portal for users to be able to sell PRE tokens to advertisers.

“We will be promoting this closed loop ecosystem but it is an open standardized currency,” he notes. “It is tradable on various exchanges that community members have set up so there is the ability for people to convert the Presearch token to bitcoin which can then be converted to any local currency.”

“We see as well as opportunity to really build out an ecosystem of places for people to spend the token as well,” he adds. “So that they can exchange it directly for either digital goods or material goods through an online platform. So that’s also in the works.”

As things stand Pape says most early adopters are ‘hodlers’. Which is to say they’re holding onto their PRE — speculating on as yet unknown token economics. (As it so often goes in the blockchain space — until, well, it suddenly doesn’t.)

“There is, as throughout the entire cryptocurrency space, an element of speculation,” he agrees. “People do tend to let their imaginations run wild so there’s kind of this interesting confluence of that core base utility — where you basically have a token that is backed by advertising, something that you can really convert it to. And then there is this potential concept of the value of the network, and of having essentially some time of stake in the value of that network.

“So there’s going to be this interesting period over the next couple of years as the token economics change as we go from this nascent startup mode into more of a full on operating mode. Where the value will likely change.”

For advertisers the PRE token buys targeted ad impressions placed in front of Presearch users by being linked to keywords used by searchers (or “targeted, non-intrusive, keyword sponsorships” as the website explainer puts it).

This is the virtuous, privacy-respecting circle Presearch is hoping to create.

Pape makes a point of emphasizing there is “no tracking” of users’ searches. Which means there’s no profiling of Preseachers by Presearch itself — ads are being targeted contextually, per the current keyword search.

But of course if you’re clicking through to a third party like Google or Facebook that’s a whole other matter; and the standard tracking caveats apply.

Presearch’s claim not to be storing or otherwise tracking users’ searches has to be taken on trust for now. However it intends to fully open source the platform to ensure truly accountable transparency in the near future. (Pape says they’re hoping they’ll be able to do so in a year.)

In the meantime he notes that the founders make themselves available to users via a messaging group on Telegram — contrasting that accessibility with the perfect unreachability of Google’s founders to the average (or really almost any) Google user.

In the modern age of messaging apps, and with their ecosystem’s community-building imperatives, these founders are most certainly not operating in a vacuum.

Currently one PRE token buys an advertiser four ad impressions on the platform — which is one lever Presearch will be able to pull on to influence the value of the token as the ecosystem develops.

“Ultimately [impressions per token] could go to ten, a hundred,” suggests Pape. “That’s obviously going to change the token — and we’ll basically do that as we see the market forces at work and how many people are actually willing to sell their tokens.

“We’ve currently got a pretty strong demand side equation right now. It’s like three to one demand to supply. A lot of the people that are earning tokens are not choosing to redeem them; they’re choosing to keep them in a wallet and hold onto them for the future. So it’s an interesting experiment in tokenomics.”

“It’s super volatile, there’s so much sentiment that’s involved, that’s really the core driver of the value,” he adds. “There’s no real fundamentals yet. Nobody has established any correlation between anything.”

Presearch began life as an internal search tool built for use at the founders’ other company to reduce time tracking down information online. And then the crypto boom caught their eye — and they saw an possible incentive structure to encourage Google users to switch.

“We didn’t really see a go to market strategy with it — search is a very challenging industry. But then when we really started looking at the cryptocurrency opportunity and the ability to potentially denominate an advertising platform in a token that could be utilized to incentivize people to switch we started thinking that it was viable; we put it out to the community, we got really good feedback on the need and on the messaging.”

A token sale followed, between July and November 2017, to raise funds for developing the platform — the obvious route for Presearch to grow a blockchain-based, community-sustaining, closed-loop ecosystem.

“One of the keys was really the ownership structure and making sure that all the participants within the ecosystem are aligned under one unit of account — which is the token. Vs having conflicting interests where there’s an equity incentive as well that may run counter to that token,” notes Pape.

The token sale raised an initial $7M but lucky timing meant Presearch was riding the cryptocurrency rollercoaster during an upward wave which meant funds appreciated to around $21M by the end of the sale period.

The first version of the platform was also launched in November of 2017, with the token itself launching at the end of the month.

Since then Pape says several hundred advertisers have participated in testing phases of the platform. A new version of the platform is pending for launch “shortly” — with a different ad unit which will arrive with a dozen “curated sponsors” on board. “There’s more brand exposure so we really want to be selective in the early days and making sure that we’re only partnering with aligned projects,” he adds.

Almost a year and a half on from the original platform launch Presearch has just made good on the number one community ask: Browser extensions to make the platform easier to use for search.

User surveys showed the biggest reason people dropped out was ease of use, according to Pape.

The new extension is available for Chrome, Brave and Firefox browsers, and works to shave off usability friction. Previously beta users had to set Presearch as their homepage or remember to type its address into the URL bar before searching.

“There’s a really good alignment of the core community but ultimately it does come down to changing user habit and behavior and that is always challenging,” he adds. “This new browser extension enables them to use the browser URL field or the search field and basically access Presearch through the UI that they’re used to and that they’ve been demanding.

Around a quarter of sign-ups stick around and become active users, according to Pape — who dubs that “already really high”. The team is expecting the new browser extensions to fuel “significant” further growth.

“We are getting ready to push it out to the users through email — [and anticipate] that we’re going to see a significant increase in the percentage of users utilizing it. And if that assumption holds through and everything really holds out we’re going to do a much more active push to grow the user base.”

They also launched an iOS Presearch app last year which taps into the voice search trend. Users can speak to search specific services with a library of sites that can be added to the app to enable deep searching of web resources, as well as apps running locally on the device. (So, for example, you could tap and tell it to ‘presearch Google Maps for London’ or ‘Spotify for Taylor Swift’.)

Competition concerns attached to the convenience of voice search — which risks further flattening consumer choice and concentrating already highly concentrated market power given its focus on filtering options to return just one search result — is an area of interest for antitrust regulators.

Europe’s antitrust chief Vestager said in an interview earlier this year that she was trying to figure out “how to have competition when you have voice search”. So perhaps Presearch’s federated platform approach offers a glimpse of a possible solution.

Global community vs Google

Pape sums up the overall competitive positioning that Presearch is shooting for as “Google for usage, DuckDuckGo for positioning”.

“We have been focused on the cryptocurrency community but there’s a really big opportunity to help all these other content providers, internet service providers,” he argues. “There’s all this traffic that is happening and it’s currently defaulting over to Google with really no compensation to the publishers — or to the tech provider. And so we’re going to be going after those opportunities pretty aggressively to get people to basically replace Google as the default that they use if they’re linking in an article to some more information or if they are an ISP and they have an error page that shows up if somebody types in a URL wrong or types in a strange query or something. Rather than have it go to Google, have it go to Presearch.”

Trying to make crypto more accessible is another focus. So there’s a built-in wallet to store PRE tokens — meaning users don’t have to have their own wallet set up to start earning crypto. (Though of course they can move PRE into a different wallet if/when they want.)

“As far as geographies go it’s a global audience but there’s a pretty heavy contingent of users in Central and South America… Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela,” he adds, discussing where early interest has been coming from. “There’s a lot of crypto adoption that’s happening down there due to this [combination] where they’re super tech savvy, they’ve got really great infrastructure, but they are still in a developing nation. So any of these types of crypto opportunities are very significant to them.”

While Google remains the staple default search option Presearch does offer its own search engine — leaning on third party APIs for search results.

Pape says the plan is to switch from Google to this engine as the default down the line. Albeit they can’t justify the switch yet.

“We want to provide users with the best search results to start,” he concedes, before adding: “Up until just recently Google’s results were certainly superior; now we think we’ve got something that is actually quite competitive.”

He couches the Presearch engine as “very similar to DuckDuckGo” but with a couple of “unique features” — including an infinite scroll view, rather than having search results paginated. (“As you’re scrolling it will automatically refresh the results.”)

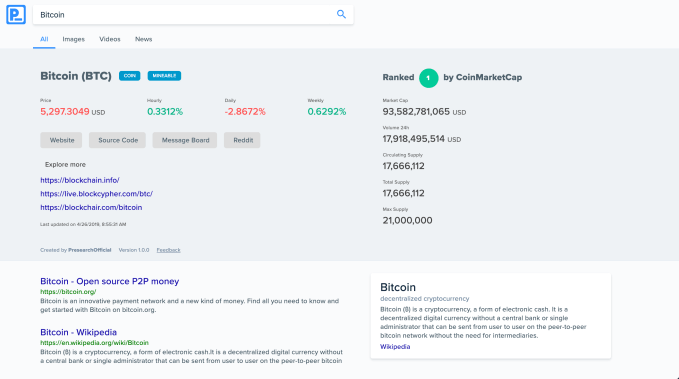

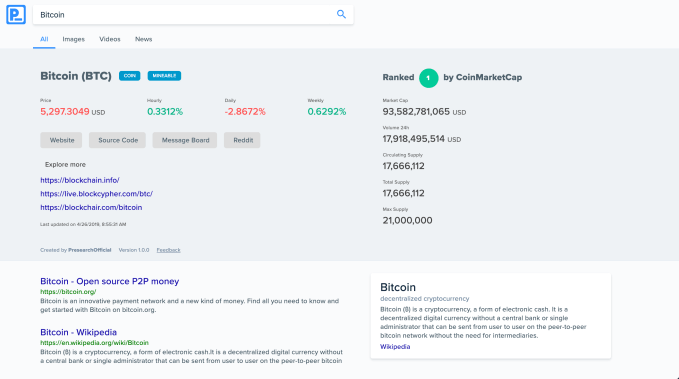

“But the biggest thing really is that we have these open source community packages so anybody can submit to us a package that would get triggered by certain keywords and basically show up with results at the top of the search.”

An example of one of these community packages can be seen by conducting a Presearch for “bitcoin” — which returns the below block of curated info related to the cryptocurrency above the rest of the search results:

Another example is currency conversions. When a currency conversion is typed into Presearch as a search query in the correct format (using relevant acronyms like USD and CAD) the query will surface a currency converter built by community members.

“It’s basically enabling anybody who knows HTML or Javascript to participate within the search ecosystem and add value to Presearch,” adds Pape.

The ultimate goal with the Presearch engine is to offer fully community-powered search where users not only create content packages and build out wider utility that can be served for particular keywords/searches but also curate these packages too.

The aim is also to have the community manage the entire process — such as by voting on what package should be the default where there are conflicting packages; and/or voting to approve package updates — much like Wikipedia editors work together on editing the online encyclopedia’s entries.

Pape notes that users would still be able to customize their own search results, such as by browsing the full suite of approved packages and selecting those that best meet their needs.

“The whole concept of the search engine is really more about user choice and giving them the ability to actively personalize their search results, and choose which contributors within the ecosystem they want to support,” he adds.

Of course Presearch is a very long way off that grand vision of wholly-community-powered search. So for now community packages are being curated by its core dev team.

Nor is it the first startup to dream big of community-powered and owned search. Not by a long, long chalk. It’s an idea that’s been kicked around the block many times before, even as Google’s dominating grip on search has cemented itself into place.

The level of crowdsourced effort required to generate differentiating value in the Google-dominated search space has proved a stumbling block for similarly minded startups wanting to compete head to head with Mountain View. And, clearly, Presearch will need a much larger user base if it’s to build and sustain enough community contributions to make its engine a compellingly useful product vs the usual search giant suspects.

But, as with Wikipedia, the idea is to keep building utility and momentum in growing increments. With — in its case — crypto rewards, backed by $21M in initial token sales, as the carrot to encourage community participation and contribution. So the founder logic sums to: ‘If we build it and pay people they’ll come’.

It’s worth noting that despite the community-focused mission Presearch’s current corporate structure is a Canadian corporation.

It does have a plan to transition to a foundation in future — with Pape envisaging distributing ~90%+ of the revenue that flows through the ecosystem to the various constituents and participants (searchers; node operators; curators; subject matter experts contributing to information indexes etc, etc), and retaining around 10% to fund operating the platform entity itself.

This is a structure familiar to many blockchain projects. Though Presearch is perhaps a bit unusual by being initially incorporated as a business.

“A lot of the crypto projects have done this foundation route [right off the bat] but really it’s more about taxes and it’s more about jurisdictional arbitrage and trying to minimize the potential regulatory risk,” Pape suggests. “For us, because of the way that we launched it, and our legal advisor [Cameron-Huff] — the founding lawyer for Ethereum — he gave us some really good guidance right out of the gate. And we’ve treated it as a business.

“We think we’ve got a really strong legal position and so we really didn’t need to do the offshore stuff at first. We figured we would get the usage and build up the core token economics. And then switch to an actual truly community-governed foundation, rather than a foundation in name which is governed by all the insiders — which is really what most of the crypto projects currently have done.”

For now Pape remains the sole shareholder of Presearch. Transitioning that sole ownership into the future foundation structure is likely a year out by his reckoning.

“One of the key concepts behind the project is ultimately providing an open source, transparent resource that is treated like more of a utility, that the community can provide input on and manage,” he adds. “So we’re looking at all the different government options.

“There’s a lot of technology being developed within the blockchain space right now. And some best practices that are starting to emerge. So we figured that we would give it a little while for that technology and those practices to mature and then we would be able to do that transition.”

.

.